Sundance 2021: A GLITCH IN THE MATRIX offers a glimpse into the unknown and ourselves

Directed by Rodney Ascher

Runtime: 1 hour 48 minutes

Currently playing at Sundance, digital rental starts 2/5

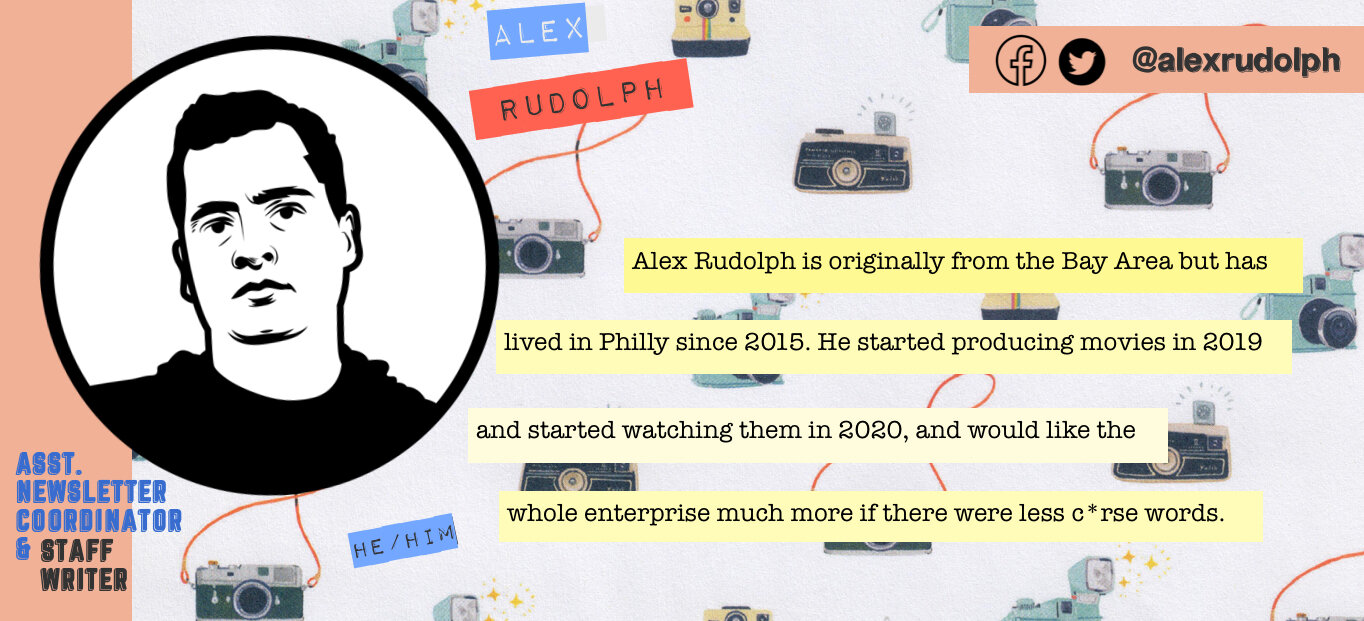

by Alex Rudolph, Staff Writer

We may be living in a simulation. It's possible I'm writing these words to a bunch of computer programs designed to elicit emotions in me, or that we're all real but we're all stuck in the same society simulacrum or that you're real and I'm the program, that I only exist to collide with your day and tweak it in tiny ways. I'm of the opinion that this is all possible but that it doesn't really matter. If it's a fake reality, it's still the only one I've ever known, and as long as it doesn't crash, as long as I don't start hitting the barriers, the barriers don't bother me. It's like if you told me the color I think of as orange was actually blue–maybe, but how does that change anything about the way I've lived for the past thirty-one years or how I'll live going forward? Rodney Ascher's fascinating new documentary, A Glitch in the Matrix, is about people who think about the simulation every day. They read academic papers, lead normal lives, try to find the seams in the fabric and wonder what finding those seams would mean.

Ascher shows most of his subjects through complicated filters (one looks like Anubis, another like a sun-headed lion gladiator), assumedly because friends and family would be weirded out knowing [X] thinks of them as a complicated Sims character. It's a clever way to put the unincorporated people of the simulation at ease and make sure they're totally willing to open up. And Ascher doesn't condescend to their ideas. Glitch is about what it's like to get deep into a conversation about simulation theory, but at no point does it try to convince you of its validity or, alternately, laugh at the people expressing those ideas.

This is, perhaps, because Ascher and his interview subjects continue to emphasize that we don't know what we don't know. As our initial speaker, the gladiator, explains, when people learn new things, we gain the tools to re-evaluate everything we already learned. The invention of the aqueduct and then the telegraph and finally the computer have radically altered the ways we think about our bodies, and it would be naive to suggest we don't have any learning left to do. Before we understood the nervous system, we were sure thoughts came from water; whatever comes ten steps after computers could shift that understanding to places we haven't imagined.

Well, places you and I haven't imagined. The film is named for a line in contemporary simulation theory ür-text The Matrix, but Ascher's primary resource is a wild speech Philip K. Dick gave at a conference in Metz in 1977. You can watch the entire thing online, but Ascher soundtracks a few excerpts in Glitch with Suicide's sinister, uncomfortable "Che," which turns out to be the best way to experience anything. Dick, a genius who was then working through years of heavy drug use and mental illness, tells the assembled crowd that they're all in a simulation and that some of his novels were either memories of past lives, premonitions of things to come or both. Crucially, he notes early on that he has no way of proving what he's talking about and could be making everything up.

He's the smartest person in the room. He also, though Ascher doesn't bring this up, had an incredibly terrible life. Dick was divorced five times, was abusive to some of those women, tried to kill himself at least twice, lost physical and mental fortunes to drugs. He wrote some of my favorite books (thanks) and thought he was trapped in pieces of most of them (sorry). It must be lonely, thinking you're locked in a metaphysical Hell.

Exploring that melancholy in his subjects ends up being Ascher's masterstroke. Multiple speakers come from religious backgrounds and hold onto a longing for something bigger. Comics monster-brain Chris Ware is interviewed about playing Minecraft with his daughter and of course finds a way to compare it to being dead. One person self-identifies as a NPC (non-player character) because his grocery store job provides him such limited, specific ways to interact with other people that he feels he's lost his internal life.

Simulation theory can even lead to violence. If you think everybody is binary mushed into a body shape, if they're going to disappear when they die, a shooting doesn't hold the same consequences it should. In a sequence that's somehow both visceral and technically spare, we float through a 3D model of a suburban home and slowly realize that one of our speakers, who we haven't seen on screen, is calling from prison, where he's serving life for killing his parents. He watched The Matrix on loop the way some of us watch gifs and he loaded a shotgun and that was it. We learn, in this unbroken digital shot, how he tried to connect with the "real" Matrix and escape the simulation. I don't know how long it is, but it felt like 15 minutes. The speaker was diagnosed with a form of schizophrenia, but Ascher never tries to blame that or any movie for the crime. He isn't spitting venom. He's just showing what happened when an irrational idea was thought through to an irrational conclusion.

Erik Davis, co-editor of Philip K. Dick's posthumous Exegesis, points out that we discuss the author's predictive abilities the way we do every other prominent science-fiction writer's-- he thought of the Internet and driverless cars! Dick's true brilliance, Davis argues, was an insight into how all of this would make us feel. He nailed the way technology seems trustworthy but will always further break us.

And the technology is broken. Word didn't automatically save for me and I had to rewrite the first two paragraphs of this review. I don't have to tip my door to leave in the morning, but Dick was never trying to say that would happen. He was communicating the texture of these things. Davis also explores Dick's empathy. Almost all of his stories are about a deep need for connection. People need people and everything else is in the way. Ascher, who's now three-for-three in making great documentaries, just happens to be documenting the real world, unfortunately. We don't have the benefit of a caring plotter, and believing in simulation theory is yet another way living in 2021 can break your heart.