Interview: Dan Gildark, director of queer horror film CTHULHU

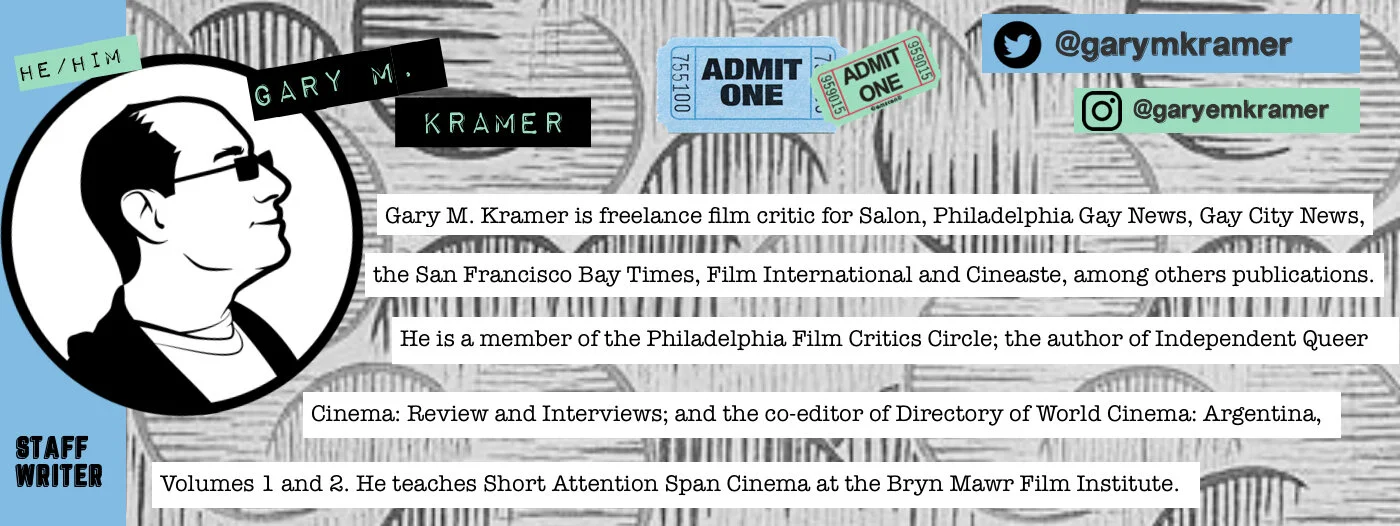

By Gary M. Kramer

Director Dan Gildark’s absorbing 2007 thriller, Cthulhu, is inspired by the H.P. Lovecraft story, The Shadow over Innsmouth. It opens with Russell (Jason Cottle), a Seattle history professor, reluctantly returning home to attend his mother’s funeral. When he encounters a car accident on the way, it is the first of many eerie moments.

Russell is estranged from his father, Reverend Marsh (Dennis Kleinsmith), who objects to his son’s homosexuality. But he does find some comfort—of a sexual nature—with his old friend Mike (Scott Patrick Green), a divorced dad. However, Russell also is preyed upon by Susan (Tori Spelling), who has a specific interest in him.

Things really start to get strange when Russell has an uncomfortable exchange with Dannie (Cara Buono) a clerk who tells him about her missing brother. As Russell investigates, he makes a startling discovery that leads to a series of unsettling events and Russell becoming unglued. (Cottle goes all-in with his performance).

Gildark spoke with MovieJawn about making his queer horror film, which is available to watch for free on YouTube here.

What prompted you to adapt Lovecraft’s story The Shadow over Innsmouth, which is part of the Cthulhu Mythos, with a gay central character? The film uses sexuality/homophobia as a metaphor.

I had a creative partner Grant Cogswell—he was staying with me in Portland, and he was a great writer—and I said, “Write me a screenplay.” At the time it was the Bush presidency, which we thought was the pinnacle of awfulness. He’d done some journalism with the [Seattle alt weekly] The Stranger, and travelled with the Black Bloc, an anarchist group. Some of them were reading Lovecraft. Grant had never read it before, and he realized it was really capturing the moment—the deep feeling of powers that are influencing our lives in ways we can’t understand. It really tapped into that. That was the first impetus. The second was reflecting people we knew. I’d previously lived on [Seattle’s] Capitol Hill, which at the time was the center of gay culture and art culture. Poets were talking to architects, who were talking to dancers, and it was comingling in interesting ways. A lot of people left small town America to get away and find another form of family through the gay community or arts, or both. As he started writing the story, and developed it, it was about capturing an outsider story of people trying to adapt and fit in and were kind of shunned. Those were our friends. So, it was taking that Innsmouth story, of being an outsider, and coming back and finding your family, and not being able to escape who you are underneath. Lovecraft’s true horror is, “Your blood is your blood.” So, it was dealing with those issues and feelings.

How queer did you want to make the film? Were you intentional on how gay the film could be? Were there concerns about not alienating the horror crowd, but still giving gay viewers some visibility?

Half of the comments about the film lambast me for making a queer film, and the other half love and associate with it. As far as how queer we wanted to make it—for me, I very much wanted to have a character that I’d not seen: he just happened to be gay. It’s just a facet of who he is. I wanted to bring that into the mainstream. I wanted him to be very human and relatable. We know it would appeal to horror kids. It was made at the dawn of internet culture where people were commenting on things, and it made a lot of fanboys angry. And it made them angry not just because it was gay, but that we were in Lovecraft’s sandbox. Fanboys are protective of their sandbox. That we were there, even exploring this element of horror, upset a lot of people. We played at Frameline [San Francisco’s gay film festival] and other gay film festivals. But I couldn’t get a sense of the time of how it was resonating in gay culture—if it was being embraced, shunned, or even being seen. It never had wide distribution. It was always curious to me how people were seeing it and if it was resonating at all.

Can you talk about the use of space and creating the film’s atmosphere and the surreal landscape which is frequently quite sinister?

A lot of that is informed by being in Seattle, when there are big open spaces. I wanted to capture the wandering, the big open spaces, and loneliness that Antonioni does. I wanted the landscape to capture Russell’s inner loneliness and be reflected that way, and the world in general, where there is abandonment. The net shed [location] was mostly empty, so we were able to use it. When we got to Astoria [Oregon], the downtown was very much abandoned. An advantage of independent film is that you can take time to find great locations. We really took our time looking up and down the Oregon and Washington coast for these types of spaces.

There are several unsettling and supernatural sequences—from an episode involving Dannie (Cara Buono) to a sequence underground that features strobe-like flashes. Can you talk about creating the horror elements?

When we wrote the script, we had a bunch of images in our mind that we want to capture, things that are uncanny or unsettling in certain circumstances. You build on the familiar and twist on it or add something you don’t expect. They all developed differently, and I worked with the cinematographer and production designer to capture what was on the page. The underground sequence, I was particularly proud of that, because I wanted to have complete darkness. In Hollywood films you can hear producers scream, “We paid for this, we want to see it!” I worked hard with my editor to know what that flash would look like, and how your eye responds to a flash, and the negative color flashes on your retina. The other element is the soundtrack. Willy Greer, our composer, scored the film. We worked with him on how to develop the soundtrack and the scares.

What about the film’s tone? It is dramatic, romantic, suspenseful, horrific—it keeps shifting and viewers must recalibrate. There is also a dystopian feel to it. How deliberate was your approach?

This was my first film, so there’s very much an element of kitchen sink—throwing a lot of my loves and references into the film, which is why you get a lot of the different tones. For horror, certainly, Rosemary’s Baby, the original Wicker Man, and more of the apocalyptic films. The Carpenter movie, The Fog, has an Innsmouth feel to it. I tried to create space so the viewer has a psychological understanding of the space they are in—on an island in a small town. That dystopian, postapocalyptic element resonates with me. We wanted to scale it out—the isolation of the village [moving to] the real world event. We tried to make it timeless, and not date it. I always like that disconnect—not steampunk—but people who try to live in the old ways in the world with all the technology that is going on. The radio voiceovers in the beginning were influenced by Children of Men, the whole “Day 2000 of the Battle of Seattle.” What sticks is what you see. Hopefully it builds the world you are in. Tonally, it comes down to the story. I wish I had more tender moments with Russell and his sister. You have to have those human moments to make you care.

There film is very much about the past influencing the present, from Russell’s frustrated relationship with Mike, or his situations with his family, it is about how little has changed from when he was last in town. Can you talk about this theme in the film?

What you are really rubbing up against is Russell’s past colliding with his present and his future. Again, the whole metaphor of trying to escape who you are—you leave small town and your family, and you make new friends and build a new family, wherever that may be, but your past is still part of you. This was him going back to deal with that. But it’s the question—do we ever escape our past, our shadow self of who we were and who we always carry with us? And how much do we want to? A lot of that gives us strength—who we were and what we fought against when we were younger or other periods in our lives. As far as the technology—I wanted to capture that cultish, old-world feel of the cult and the town, but it was to emphasize his past, and provide a more graphic representation of his future and present colliding with the past.