Ani-May: Demon Slayer provides just the right combination of comfort and blood splatter

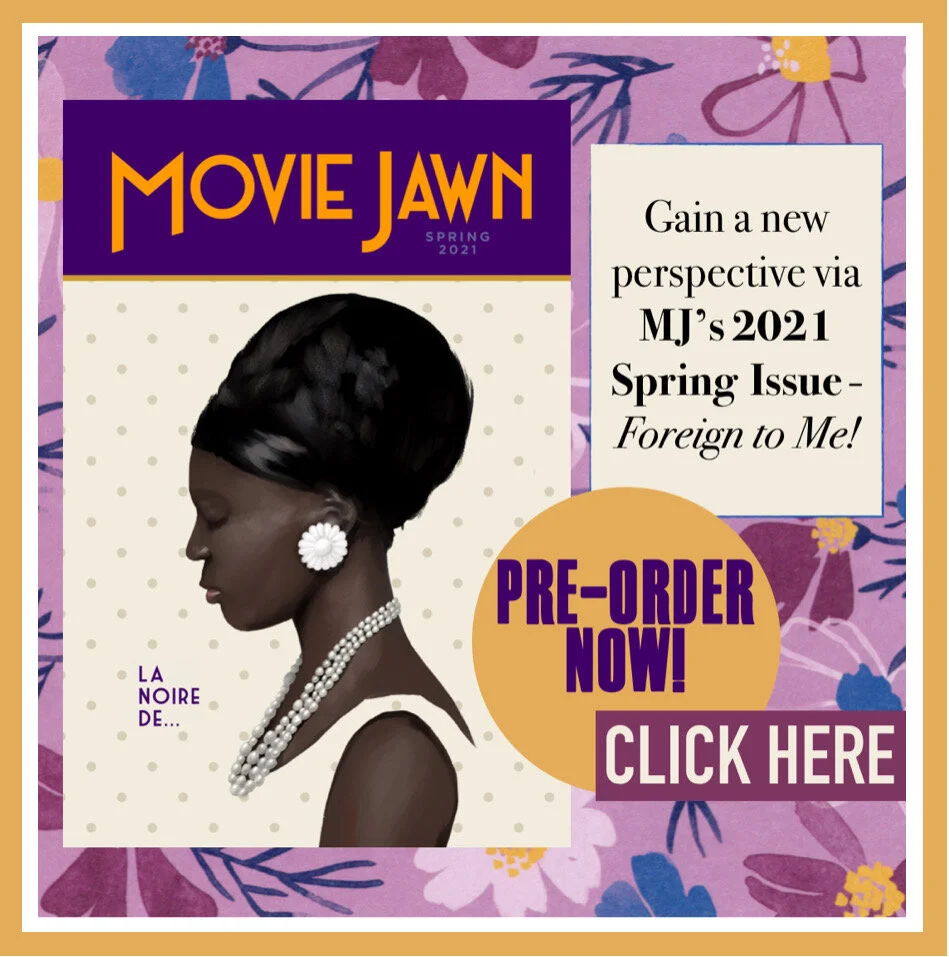

This month, we’re celebrating animation from Japan–better known as anime–by looking at some of our favorite works or ones we hope will provide new perspective. This also ties into our upcoming Spring issue of the zine, which is all about gaining new insights through films that are ‘foreign to us.’ See all the articles here.

by Ryan Silberstein, Managing Editor, The Red Herring

Similar to Emily, I was original generation Toonami watcher, and the programming block broadened my interest in anime beyond the Pokémon fad through the likes of Dragon Ball Z and Gundam Wing shortly after Cartoon Network’s programming block launched in 1999. I was about to enter high school, and keeping up with shows that aired five days a week wasn’t too hard. My interest was short-lived, however. Other than my continued interest in the output of Studio Ghibli, I mostly stopped paying attention to anime before I even finished high school. None of my close college friends were fans and I had plenty of other things to occupy my time. Besides, until the streaming age came about, being an anime fan meant sinking a lot of money into expensive DVDs or pirating and hoping the (often fan-made) subtitles were accurate.

Other than the aforementioned Ghibli films, the only other anime I had really taken in as an adult was the excellent Your Name. and last year’s new Lupin the Third entry. Your Name. had piqued my interest when it set box office records in Japan, and Lupin was a new entry in a series I was familiar with thanks to The Castle of Cagliostro, which was Hayao Miyazaki’s directorial debut. Recently, in my ongoing search for comfort watches during the pandemic, I found that my favorite Gundam series–Mobile Suit Gundam: The 08th MS Team–was streaming on Hulu, I enjoyed it even more than I had when I was in high school, which led me to seeking out more from that franchise (I will always have a soft spot for mecha).

So when I saw that Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba the Movie: Mugen Train had unseated the beloved Spirited Away as the all-time highest grossing film in Japan, I was primed and ready. In doing some reading, I learned that Mugen Train took place after the first season of the Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba series, which comprised 26 episodes. The show debuted in Japan and around the world in 2019, and I was happy to discover it was streaming on both Hulu and Netflix. The low barrier to at least some popular anime series is one of the few things that still surprises me in the streaming age, especially when I know there are whole services dedicated to the medium. So I blazed through every episode and after my second vaccine dose, caught a (almost empty weeknight) showing of Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba the Movie: Mugen Train.

What turned Demon Slayer into a phenomenon? From what I understand about Shōnen manga and anime–a genre that is designed to appeal primarily to teenage boys and often has a focus on action–there isn’t anything in Demon Slayer that truly breaks the mold. Rather, the show’s particular flavor and focus makes it resonate beyond that target audience, and particularly given the challenges we’ve all faced in the last 12 months. I keep telling myself that I won’t resort to using the pandemic in my writing, but this feels right.

I have noticed in my own viewing patterns that the things that have made me happiest during the pandemic are things that provide a mix of the novel and the familiar. Watching every film in the Showa-era Godzilla Criterion set or all the Kong movies, and playing the remake of The Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening on my Switch are all examples of this idea. The part of me that wants to experience something new is just as satisfied as the part of me that craves the comfort of familiarity–or nostalgia. Demon Slayer is that exact kind of comfort, sticking close enough to genre conventions and formulaic storytelling to provide comfort while also providing enough new to feel fresh. Combined with the particular characteristics of its main character and premise, and you have one of my favorite things I have tuned into in the past year.

Okay, so what is Demon Slayer actually about? The show takes place in Taishō-era Japan (1912-1926), placing it an interesting point of modernization (cities seem to have electricity, but more rural areas do not, some characters have never seen a train before). Our main character is Tanjiro Kamado, a kind boy who lives outside of a mountain village, earning money for his family as a charcoal salesman. One day when he returns to his village, he finds his family has been attacked and slaughtered by a demon, save for his sister Nezuko. She seems to have retained some of her humanity, and after meeting a member of the Demon Slayer Corps, Tanjiro decides to train to become a member while searching for a way to turn his sister back into a human.

While the show’s opening episode mixes a celebratory small town feel with gory tragedy, most of the show maintains a lighthearted adventure feel. Eventually Tanjiro learns to tap into some cool fighting techniques, and is joined by the cowardly Zenitsu and Inosuke, a wild spirit (he is constantly shirtless and wears a boar’s head mask). Once being accepted into the Demon Slayer Corps, the foursome are given orders via talking crows about which demons to track down and uh, slay. This structure forms the backbone of the series arcs, allowing for varied settings and challenges for our heroes. Each of the characters has an enhanced sense–Tanjiro can smell really well for example–and the demons also have unique abilities or fighting techniques. The familiarity in this pattern isn’t dissimilar to video games (with the demons standing in for boss fights) or series like Dragon Ball Z. The movie Mugen Train is essentially just another arc of the show told in a really tight two hours that puts them in a restrictive setting.

All of this is brought to life with dynamic animation. The way that traditional animated styles are blended with computer imagery is clever and rarely distracting, even when incongruous. The character designs are especially strong across the board, with each of them being unique but all feeling like they come from the same universe. The demons are a bit more wild than the humans, and their extra odd nature is emphasized. The action is also well-done, and the series embraces stylized violence in a very satisfying way.

But why I’ve become so strongly attached to Demon Slayer has everything to do with Tanjiro. All my life I’ve been more into the goofy sidekick characters than the more stoic leads (my favorite Ninja Turtle was Michelangelo). While so many other genre heroes are burdened with destiny, or trying to avenge some wrong they feel guilty over, Tanjiro’s defining trait is his empathy. The series treats his beheading of demons as a way of releasing their original forms from the curse of immortality. Even the demons that seem to relish the violence and killing of humans are given at least some shading that reveals a sense of longing, if not outright regret. After all, Tanjiro isn’t questing for power or vengeance. He’s fighting for a cure. Seeing someone fight and dedicate their life to helping others (even if it involves a lot of sword play), felt more meaningful that it might have been pre-pandemic. Tanjiro’s empathy and caring extends to everyone he meets from friends to demons to shopkeepers. It even occasionally drives some of the story’s more comedic moments. The kindness at the core of Demon Slayer is a welcome balance to the action, and one reason I think it has resonated with so many people, myself included.