PONETTE is a beautiful something left behind in Jacques Doillon’s classic view into a child’s grief

Directed by Jacques Doillon

Written by Jacques Doillon and Brune Compagnon

Starring Victoire Thivisol, Marie Trintignant, and Xavier Beauvois

Runtime: 97 minutes

Available on Blu-ray and DVD from Kino Classics starting May 25, 2021

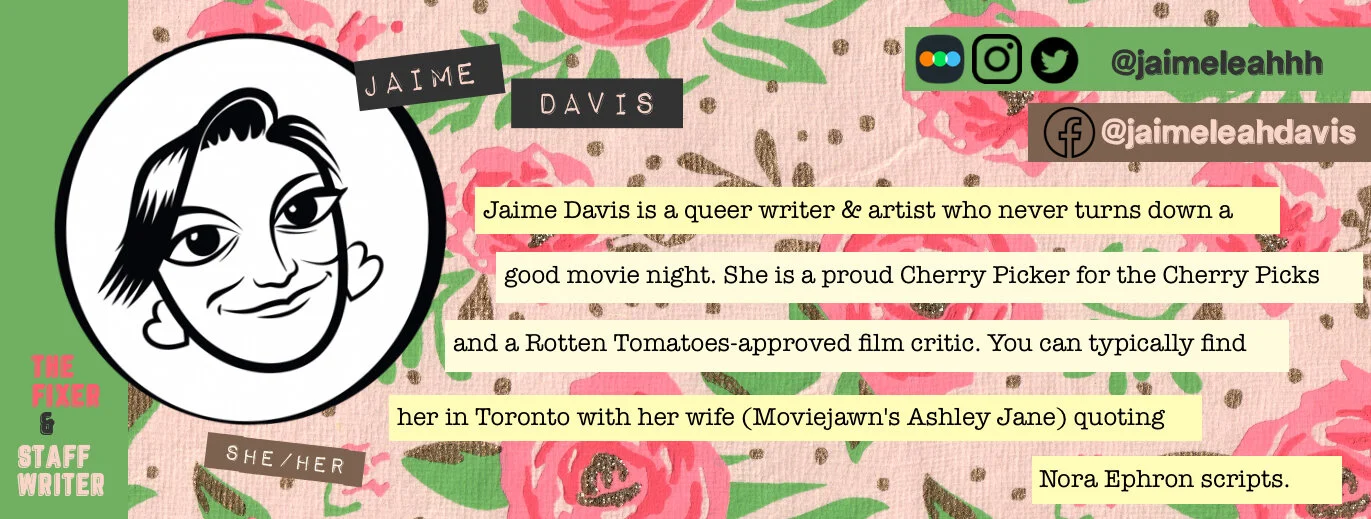

by Jaime Davis, The Fixer

What does a child think about death? What do they hear when we talk tough topics with them, like death? How do they process grief in the shadow of adults who may be doing the same? Jacques Doillon’s sincere, heartfelt Ponette explores all of this from a child’s perspective with so much tenderness and care. It’s a film that’s haunted me for the past 21 years, ever since I first watched it in college.

It was around 1999 or 2000–I can’t remember exactly–just another ordinary term in an ordinary school year at Temple University in Philadelphia. I was 19 and a film major, but I didn’t see or learn about Ponette in any of my film classes–instead, it was in one of my French courses, which was a regular language course with a tiny bit of culture thrown in for good measure. The professor, Mélanie Péron, was a recent transplant from Paris who had met a Philadelphia-native, fell in love, married, and relocated with him to the area. My friends and I of course loved her–she was a real French person, from Paris! Madame Péron was a chic grown-up, not too much older than us, with the coolest sneakers I had ever seen. Needless to say, we all wanted to be like her when we grew up.

There was this one particular Monday morning class where two remarkable things happened. Madame Péron had just come back from a quick weekend trip to visit her family in Paris and she brought back a fresh croissant for each student in our class. Each croissant was carefully and individually wrapped in plastic wrap to preserve it for the journey home. I’m not entirely sure how she managed to bring them on the plane with her, and we couldn’t have been the only section of the course she taught, so the gesture felt extremely caring and special. At that time, I had never even been out of the country before, nor did I feel particularly ready to–I was extremely shy growing up, even through college, and the thought of going to a country where I didn’t know the language thoroughly frightened me (I’ve gotten over this to an extent, thankfully). Despite having moved to seven different US states as a kid, my worldview was quite narrow–I hadn’t yet explored the foods and films and culture of other places. So to me, this very simple croissant represented something way beyond a delicious baked good…it was a window into another world. I know you can get croissant pretty much anywhere, but to Young Baby Jaime this was a Very Big Deal.

Madame Péron may have been tired from her quick trip abroad that morning because instead of her normal lecture and repetition she decided to play a movie for us: Ponette. She told us it was one of the best new French films, so we all carefully munched on our special croissants while immersing ourselves in Jacques Doillon’s now-classic exploration of death from the POV of children. The story centers on four-year-old Ponette, whose mother has just been killed in a terrible car accident. Her father deals in the best way he can (which is not entirely the best way for Ponette), first leaving her at the country home of her aunt and two young cousins while he sets off to work in Lyon, about two hours away, before all three children are sent to a local boarding school. Ponette spends a little over an hour and a half painfully yearning for her mother, reuniting with her in dreams and at the cemetery where she’s buried. During the long stretches when her mom doesn’t come for her, Ponette veers between curiosity towards the afterlife and desperation at not seeing her mother again. Her precocious cousins, Delphine and Matiaz provide little help, regurgitating random Bible teachings they’ve most likely overheard from their mother. Matiaz is adamant that she won’t see her mother again, because the dead can’t wake up, oh so charmingly telling her at one point, “Je déteste les morts.” Delphine appears to toy with Ponette, explaining that if she’s good and gathers presents for her mom, she’ll come. But of course, she doesn’t.

Throughout the film, adults and children alike explain their beliefs about death to Ponette and it’s up to the young girl to piece things together for herself. She sets out on a path of self-discovery, enduring a young boy at school accusing her of killing her mom by being bad, embarking on a series of tests created by her Jewish friend Ada in order to speak to God, and eventually, her mother. She’s even instructed by her father to ignore all this God talk before later being taught to use magic to bring her mom back from her roommate, Luce. As you can imagine, this is quite the harrowing journey for one so small, and as an audience member, you become fully immersed in each of Ponette’s steps along the way.

As a director, Doillon is known for his use of realism and work with unknown or non-professional actors. Ponette is quite a filmmaking achievement in this regard – though the cinematography and style are fairly simple, the acting is breathtaking. Victoire Thivisol was only four when she began filming as the title character, and her acting is so believable, so true, that you almost forget you’re watching a narrative feature. She went on to do a bit more acting, most notably as Juliet Binoche’s daughter in a little film called Chocolat (which as many know, is delightful).

One of my favorite aspects of Ponette is how Doillon chose to visualize this world by keeping the camera almost entirely at children’s height. Even when adults are in the frame, often they’re bending down to speak with their tiny costars. Only a few times does the camera move up, like when the dad scoops up a young Ponette into his arms. Another thing I love is just how quiet the film is – there is the presence of a score but it’s used sparingly, allowing you to instead focus on whatever Ponette is currently working out for herself and her grief. It reminds me quite a bit of recent documentary Beautiful Something Left Behind, which similarly investigates grief experienced by children after the death of a loved one (please read my wife’s beautiful review here). Ponette is starkly heartbreaking, a must-watch if you haven’t yet seen it, and thanks to Kino Lorber, available on home video starting May 25th on its Kino Classics label.

My first time watching the film, in a small classroom at 19 years old, I felt like the world opened up to me just a little. Or maybe I was the one opening up to the world, as I cried my way through it, tears spilling onto my croissant as I teared off little pieces and savored it, bit by bit. I owe a big thank you to Madame Péron (who’s still a French professor by the way – I emailed her a few years ago to personally thank her). She introduced me to my first foreign film, instilling a hunger in me to explore different countries and viewpoints and culture through movies. I will never forget her class just as I will never forget little Ponette.