The British New Wave: The Loneliness of the Angry Young Man

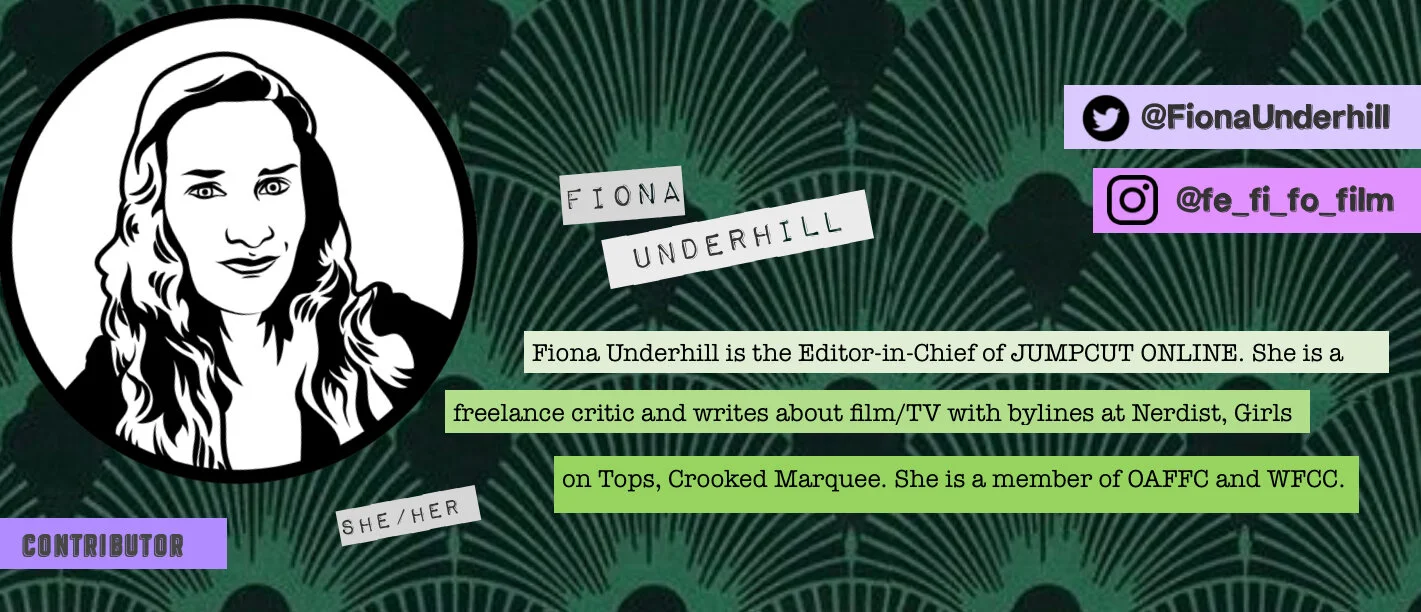

by Fiona Underhill, Staff Writer

The British New Wave of the early 60s has never had the same cachet as its French namesake but, for me, it is much more significant. Unfortunately, even to this day, it is the only intensive period of British film history that actually gave a crap about working class characters. The UK film industry is now dominated by privately-educated actors and period dramas overwhelmingly concerned with white middle-and-upper class characters (which I love, but I also love contemporary, urgent filmmaking that offers some variety and diversity). For a five-year period, from 1959 to 1963, the ‘Angry Young Men’ movement from British theatre (led by playwright John Osborne) was brought over to film, chiefly by director Tony Richardson. Also known as ‘kitchen-sink dramas,’ these were social realist films that depicted characters in The Midlands (where I’m from) or The North working in factories, living in cramped conditions and seeking relief through booze, sex and criminal activities.

Two of these films have a uniquely working-class spin on sport. This Sporting Life concerns a Rugby League player in Wakefield. While Rugby Union gets its name from the elite school of the same name and is generally played by posh people, Rugby League is popular throughout Yorkshire and Lancashire and is generally viewed as a faster, rougher and tougher sport. In The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner (Tony Richardson), a Borstal inmate (equivalent of ‘juvie’ in the US) is encouraged by the governor (played by Richardson’s father-in-law, Michael Redgrave) in his cross-country running, specifically so he can beat runners from a local private school in a race. The governor even runs the Borstal on the private school model - it’s called Ruxton Towers and has a house system with house captains and inter-house sports (I taught at an all-boys school for ten years that also had this system). He clearly believes that a bit of healthy competition will soon sort these misguided whippersnappers out.

As well as sport, these young characters also have a love of the arts. The best aspect of these films is that the working-class characters get rich inner lives, full of appreciation of poetry, music and theatre. Richard Burton’s Jimmy in Look Back in Anger is a jazz trumpeter and has a little Music Hall double-act with his best friend Cliff and Music Hall is also at the center of The Entertainer. The protagonist of Billy Liar lives entirely in a world of fantasy and imagination, Rita Tushingham’s Jo in A Taste of Honey is a talented artist and even Albert Finney’s Arthur in Saturday Night and Sunday Morning has an eye for fashion. This is not an uneducated, ignorant mass, as the working classes can be portrayed in the media today. As Alan Sillitoe writes in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner book; “I’m a human being and I’ve got thoughts and secrets and bloody life inside me.”

Similarly, there is something beautiful about Colin’s relationship with cross-country running, he says “I was always trying to get lost as a kid. Soon found out you can’t get lost though.” Colin’s anecdote of trying to escape his parents as a little kid on the beach is relatable for me, as I was left in the care of an uncle on a beach once as a pre-schooler, said uncle promptly fell asleep and I wandered very far, before I was found in a hole I’d dug for myself. Colin’s girlfriend says; “I can’t understand why you’re always trying to run away from things.” But we see how unhappy Colin’s home life is and his desire for freedom is entirely understandable. He’s even allowed to run free from the Borstal - the governor’s desire to win is so strong that he allows Colin to train on his own, in the surrounding countryside. Even though it means early mornings in snow, ice, rain and mud, this freedom and solitude is worth it for Colin.

The use of sound and music is important in The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner. We hear the sound of soft plimsolls slapping on country roads before we see anything, then Tom Courtenay’s narration in voice-over, then an instrumental version of Jerusalem. This most English of anthems will become a recurring motif throughout the film, with the irony of ‘England’s green and pleasant land’ being something that not everyone has access to. Courtenay’s Colin has a complicated relationship with ‘England’s pleasant pastures seen,’ as running gives him time to think and reminisce, which isn’t necessarily a good thing.

My father died when I was three years old and I don’t have any ‘real’ memories of him, only anecdotes told to me by family members that have become facsimiles of memories. Many of the photographs that I have of him are from his time as a cross-country runner, as a teenager and young man (he was just 33 when he died). His physical similarity to Tom Courtenay in this film is uncanny – with both having the gangly frame that is suited to the sport. My father’s homelife was complicated and I can imagine that it was certainly a form of escapism, as it is for Colin. This is a large part of why this film is so special to me.

Many of the themes that are common to the British New Wave are present in Loneliness - including generational conflict and railing against the establishment. In one of the flashbacks to Colin’s pre-Borstal life, he and his best mate Mike (James Bolam) openly mock a politician on the television, as well as viewing all interactions with the police and the ‘screws’ (the guards at Borstal) as games in which they must come out on top. Colin’s disdain for the governor only really reveals itself in the denouement of the film, but in Alan Sillitoe’s book (who also wrote Saturday Night and Sunday Morning), we know Colin’s attitude from early on; “he’s stupid and I’m not because I can see further into the likes of him than he can see into the likes of me.” The funniest scene from the book (which is carried over to the film) involves Colin hiding stolen money in a drainpipe, but when the police come knocking, it starts raining and the bank notes flush out of the pipe in full view of the copper.

This collection of films, from Richardson (as well as Lindsay Anderson, Jack Clayton, Karel Reisz and John Schlesinger and writers Osborne, Sillitoe, Shelagh Delaney and Keith Waterhouse, among others) were very much the British equivalent of Actors Studio alumni such as James Dean, Paul Newman and Marlon Brando striking out as a new generation with a new artistic expression. Actors like Richard Burton, Richard Harris, Albert Finney, Tom Courtenay, Rita Tushingham and Joan Plowright also brought a new style of acting from the British theatre over to film. With the working-class concerns of this group of writers, combined with centering the viewpoint of a younger generation - the British New Wave may have burned briefly, but it certainly burned brightly. I would love to see British film focus its spotlight on the working class again and while there’s some hope – eg. Sarah Gavron’s Rocks – there needs to be so much more support to give non-posh people access to the film industry.

a list of the British New Wave films and where to stream them in the US

Look Back in Anger (dir. Tony Richardson, 1959) HBO Max/Criterion Channel

Room at the Top (dir. Jack Clayton, 1959) Criterion Channel

Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (dir. Karel Reisz, 1960) Criterion Channel

The Entertainer (dir. Tony Richardson, 1960) HBO Max/Criterion Channel

A Taste of Honey (dir. Tony Richardson, 1961) HBO Max/Criterion Channel

The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner (dir. Tony Richardson, 1962), Freevee/Tubi

Billy Liar (dir. John Schlesinger, 1963) Criterion Channel

This Sporting Life (dir. Lindsay Anderson, 1963) Criterion Channel

This originally appeared in the Summer 2021 print issue of MovieJawn. Purchase here!